What is Alzheimer’s disease?

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia. The word dementia describes a set of symptoms that can include memory loss and difficulties with thinking, problem-solving or language. These symptoms occur when the brain is damaged by certain diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease. This factsheet describes the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, how it is diagnosed, and the factors that can put someone at risk of developing it. It also describes the treatments and support that are currently available.

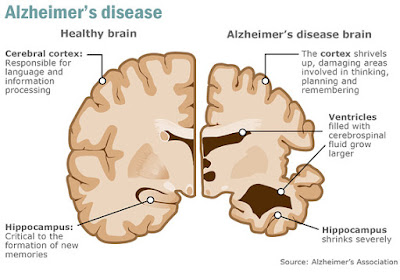

Alzheimer’s disease, named after the doctor who first described it (Alois Alzheimer), is a physical disease that affects the brain. There are more than 520,000 people in the UK with Alzheimer’s disease. During the course of the disease, proteins build up in the brain to form structures called ‘plaques’ and ‘tangles’. This leads to the loss of connections between nerve cells, and eventually to the death of nerve cells and loss of brain tissue. People with Alzheimer’s also have a shortage of some important chemicals in their brain. These chemical messengers help to transmit signals around the brain. When there is a shortage of them, the signals are not transmitted as effectively. As discussed below, current treatments for Alzheimer’s disease can help boost the levels of chemical messengers in the brain, which can help with some of the symptoms.

Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease. This means that gradually, over time, more parts of the brain are damaged. As this happens, more symptoms develop. They also become more severe.

Symptoms

The symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease are generally mild to start with, but they get worse over time and start to interfere with daily life.

There are some common symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, but it is important to remember that everyone is unique. Two people with Alzheimer’s are unlikely to experience the condition in exactly the same way.

For most people with Alzheimer’s, the earliest symptoms are memory lapses. In particular, they may have difficulty recalling recent events and learning new information. These symptoms occur because the early damage in Alzheimer’s is usually to a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which has a central role in day-to-day memory. Memory for life events that happened a long time ago is often unaffected in the early stages of the disease.

Memory loss due to Alzheimer’s disease increasingly interferes with daily life as the condition progresses. The person may:

• lose items (eg keys, glasses) around the house

• struggle to find the right word in a conversation or forget

someone’s name

• forget about recent conversations or events

• get lost in a familiar place or on a familiar journey

• forget appointments or anniversaries.

Although memory difficulties are usually the earliest symptoms of Alzheimer’s, someone with the disease will also have – or go on to develop – problems with other aspects of thinking, reasoning, perception or communication. They might have difficulties with:

• language – struggling to follow a conversation or repeating themselves

• visuospatial skills – problems judging distance or seeing objects

in three dimensions; navigating stairs or parking the car become much harder

• concentrating, planning or organising – difficulties making decisions, solving problems or carrying out a sequence of tasks (eg cooking a meal)

• orientation – becoming confused or losing track of the day or date.

A person in the earlier stages of Alzheimer’s will often have changes in their mood. They may become anxious, irritable or depressed. Many people become withdrawn and lose interest in activities and hobbies.

Later stages

As Alzheimer’s progresses, problems with memory loss, communication, reasoning and orientation become more severe. The person will need more day-to-day support from those who care for them.

Some people start to believe things that are untrue (delusions) or – less often – see or hear things which are not really there (hallucinations).

|

| Brain with Alzheimer |

Many people with Alzheimer’s also develop behaviours that seem unusual or out of character. These include agitation (eg restlessness or pacing), calling out, repeating the same question, disturbed sleep patterns or reacting aggressively. Such behaviours can be distressing or challenging for the person and their carer. They may require separate treatment and management to memory problems.

In the later stages of Alzheimer’s disease someone may become much less aware of what is happening around them. They may have difficulties eating or walking without help, and become increasingly frail. Eventually, the person will need help with all their daily activities.

How quickly Alzheimer’s disease progresses, and the life expectancy of someone with it, vary greatly. On average, people with Alzheimer’s disease live for eight to ten years after the first symptoms. However, this varies a lot, depending particularly on how old the person was when they first developed Alzheimer’s. For more information see factsheet 458, The progression of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias and factsheet 417, The later stages of dementia.

Mixed dementia

An estimated 10 per cent of people with dementia have more than one type at the same time. This is called mixed dementia. The most common combination is Alzheimer’s disease with vascular dementia (caused by problems with the blood supply to the brain). The symptoms of this kind of mixed dementia are a mixture of the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

Atypical Alzheimer’s disease

In some people with Alzheimer’s disease the earliest symptoms are not memory loss. This is called atypical Alzheimer’s disease. The underlying damage (plaques and tangles) is the same, but the first part of the brain to be affected is not the hippocampus.

Atypical Alzheimer’s disease is uncommon in those diagnosed when they are over 65. It accounts for around five per cent of all Alzheimer’s in this age group. It is, however, more common in people diagnosed when they are under 65 (early-onset Alzheimer’s disease). In this age group it represents up to one-third of cases.

The atypical forms of Alzheimer’s disease are as follows:

• Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) occurs when there is damage to areas at the back and upper-rear of the brain. These are areas that process visual information and deal with spatial awareness. This means the early symptoms of PCA are often problems identifying objects or reading, even if the eyes are healthy. Someone may also struggle to judge distances when going down stairs, or seem uncoordinated (for example when dressing).

• Logopenic aphasia involves damage to the areas in the left side of the brain that produce language. The person’s speech becomes laboured with long pauses.

• Frontal variant Alzheimer’s disease involves damage to the

lobes at the front of the brain. The symptoms are problems with planning and decision-making. The person may also behave in socially inappropriate ways or seem not to care about the feelings

of others.

Who gets Alzheimer’s disease?

Most people who develop Alzheimer’s disease do so after the age of 65, but people under this age can also develop it. This is called early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, a type of young-onset dementia. In the UK there are over 40,000 people under the age of 65 with dementia.

Developing Alzheimer’s disease is linked to a combination of factors, explained in more detail below. Some of these risk factors (eg lifestyle) can be controlled, but others (eg age and genes) cannot. For more information see factsheet 450, Am I at risk of developing dementia?

Age

Age is the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s. The disease mainly affects people over 65. Above this age, a person’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease doubles approximately every five years. One in six people over 80 have dementia.

Gender

For reasons that are not clear, there are about twice as many women as men over 65 with Alzheimer’s disease. This difference is not fully explained by the fact that women on average live longer than men. It may be that Alzheimer’s in women is linked to a lack of the hormone oestrogen after the menopause.

Genetic inheritance

Many people fear that the disease may be passed down to them from a parent or grandparent. Scientists are investigating the genetic background to Alzheimer’s. There are a few families with a very clear inheritance of Alzheimer’s from one generation to the next. In such families the dementia tends to develop well before age 65. However, Alzheimer’s disease that is so strongly inherited is extremely rare.

In the vast majority of people, the influence of genetics on risk of Alzheimer’s disease is much more subtle. A number of genes are known to increase or reduce a person’s chances of developing Alzheimer’s. For someone with a close relative (parent or sibling) who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s when over 65, their own risk of developing the disease is increased. However, this does not mean that Alzheimer’s is inevitable, and everyone can reduce their risk by living a healthy lifestyle.

For more information see factsheet 405, Genetics of dementia.

People with Down’s syndrome are at particular risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, because of a difference in their genetic

makeup. For more information see factsheet 430, Learning

disabilities and dementia.

Health and lifestyle

Medical conditions such as diabetes, stroke and heart problems, as well as high blood pressure, high cholesterol and obesity in mid-life, are all known to increase the risk of both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Anyone can reduce their risk by keeping these under control. Depression is a probable risk factor for dementia; getting it treated early is important.

People who adopt a healthy lifestyle, especially from mid-life onwards, are less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. This means taking regular physical exercise and keeping to a healthy weight, not smoking, eating a healthy balanced diet and drinking only in moderation.Leading an active lifestyle that combines regular physical, social and mental activity will help to lower risk.

Diagnosis

Anyone who is concerned that they may have Alzheimer’s disease (or any other form of dementia) should seek help from their GP. If someone does have dementia, an early diagnosis has many benefits: it provides an explanation for the person’s symptoms; it gives access to treatment, advice and support; and it allows them to prepare for the future and plan ahead.

There is no single test for Alzheimer’s disease. The GP will first need to rule out conditions that can have similar symptoms, such as infections, vitamin and thyroid deficiencies (from a blood test), depression and side effects of medication.

The doctor will also talk to the person, and where possible someone who knows them well, about their medical history and how their symptoms are affecting their life. The GP or a practice nurse may ask the person to do some tests of mental abilities.

The GP may feel able to make a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s at this stage. If not, they will generally refer the person to a specialist. This could be an old-age psychiatrist (who specialises in the mental health of older people) often based in a memory service. Or it might be a geriatrician (who specialises in the physical health of older people), a neurologist (who specialises in conditions of the brain and nervous system) or a general adult psychiatrist (who specialises in mental health in adults) in a hospital.

The specialist will assess the person’s symptoms, and how they developed, in more detail. In Alzheimer’s disease there will usually have been a gradual worsening of memory over several months. A family member may be more aware of these changes than the person with suspected Alzheimer’s is themselves.

The person’s memory, thinking and other mental abilities will also be assessed further with a pen-and-paper test. When someone with Alzheimer’s is tested, they will often forget things quite quickly.

They will often not be able to recall them a few minutes later even when prompted.

The person may undergo a brain scan, which can show whether certain changes have taken place in the brain. There are a number of different types of brain scan. The most widely used are CT (computerised tomography) and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). A brain scan may rule out certain conditions such as stroke, tumour or a build-up of fluid inside the brain. These can have symptoms similar to those of Alzheimer’s. It may also clarify the type of dementia. In a person with early Alzheimer’s disease a brain scan may show that the hippocampus and surrounding brain tissue have shrunk.

The diagnosis should be communicated clearly to the person and usually also to those closest to them, along with a discussion about the next steps. For more information see factsheet 426, Assessment and diagnosis.

Treatment and support

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, but there is a lot that can be done to enable someone to live well with the condition. This will involve drug and non-drug care, support and activities.

The person should have a chance to talk to a professional about their diagnosis. This could be a psychiatrist or mental health nurse, a clinical psychologist, occupational therapist or GP. Information on the support that is available and where to go for further advice is vital in helping someone to stay physically and mentally well. Professionals such as the GP and staff at the memory service or local Alzheimer’s Society can advise on what might best meet the needs of the individual and of those caring for them.

There are drug treatments for Alzheimer’s disease that can temporarily alleviate some symptoms or slow down their progression in some people. (The names in brackets are common brands of these drugs.)

A person in the mild or moderate stages of Alzheimer’s disease or mixed dementia will often be prescribed a drug such as donepezil (eg Aricept), rivastigmine (eg Exelon) or galantamine (eg Reminyl). The drug may help with memory problems, improve concentration and motivation, and help with aspects of daily living such as cooking, shopping or hobbies. A person in the moderate or severe stages of Alzheimer’s disease or mixed dementia may be offered a different kind of drug: memantine (eg Ebixa). This may help with mental abilities and daily living, and ease distressing or challenging behaviours such as agitation and delusions. For more information see factsheet 407, Drug treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.

If someone is depressed or anxious, talking therapies (such as cognitive behavioural therapy) or drug treatments (such as antidepressants) may also be tried. Counselling may help the person adjust to the diagnosis.

There are many ways to help someone remain independent and cope with memory loss. These include practical things like developing a routine or using a weekly pill box. There are other assistive technology products available such as electronic reminders and calendar clocks. For more information see factsheet 526, Coping with memory loss.

It is beneficial for a person with Alzheimer’s to keep up with activities that they enjoy. Many people benefit from exercising their mind with reading or puzzles. There is evidence that attending sessions to keep mentally active helps (cognitive stimulation). Life story work, in which someone shares their life experiences and makes a personal record, may help with memory, mood and wellbeing. As the dementia worsens, many people enjoy more general reminiscence activities.

Over time, changes in the person’s behaviour such as agitation or aggression become more likely. These behaviours are often a sign that the person is in distress. This could be from a medical condition such as pain; because they misunderstood something or someone; or perhaps because they are frustrated or under-stimulated. Individualised approaches should look for, and try to address, the underlying cause. General non-drug approaches often also help. These include social interaction, music, reminiscence, exercise or other activities that are meaningful for the person. They are generally tried before additional drugs are considered, particularly antipsychotics.

Anyone caring for the person is likely to find these behaviours distressing. Support for carers is particularly important at such times.

No comments:

Post a Comment